The Michigan Court of Appeals recently reversed Judge James P. Lambros when he ignored sentencing guidelines, handing down maximum sentences of 10-15 years in People v. Titus (reckless driving causing death) and People v Linklater (OWI causing death). In People v Lockridge, 498 Mich 358, 365 (2015), the Michigan Supreme Court held that the previously-mandatory sentencing guidelines were advisory only. The Lockridge Court held that Michigan’s mandatory sentencing guidelines violate the Sixth Amendment by imposing a mandatory minimum guideline sentence. The Court held that MCL 769.34(2) could not constitutionally impose a mandatory minimum guidelines sentencing range, so the Lockridge Court held that our state criminal sentencing guidelines should be deemed advisory.

With the announcement that guidelines no longer apply, some judges used this legal development as an opportunity to ignore the guidelines altogether, imposing extremely harsh sentences. Imposing a sentence that exceeds guidelines is known as an "upward departure." An upward departure has always been permissible, but it must be legally justified based upon objective facts that are not reflected in the guidelines. Numerous cases have followed Lockridge in just the last couple of years, and the higher courts have repeatedly held that a sentence must be reasonable in light of the guidelines.

With the announcement that guidelines no longer apply, some judges used this legal development as an opportunity to ignore the guidelines altogether, imposing extremely harsh sentences. Imposing a sentence that exceeds guidelines is known as an "upward departure." An upward departure has always been permissible, but it must be legally justified based upon objective facts that are not reflected in the guidelines. Numerous cases have followed Lockridge in just the last couple of years, and the higher courts have repeatedly held that a sentence must be reasonable in light of the guidelines.

The 14th Amendment to the US Constitution grants each of us "equal protection of the laws." In Michigan, the Legislature has passed laws that impose maximum sentences for crimes, along with guidelines detailing what an appropriate sentence should be based upon the offender's prior record and general variables that might pertain to the crime. It would be patently unfair for two people under identical circumstances to receive completely disproportionate sentences. In other words, an unjustified upward departure is a violation of equal protection.

People v Titus is a great example of an unwarranted upward departure. In these consolidated cases, the Michigan Court of Appeals reversed Judge James P. Lambros of the 50th Circuit Court in Chippewa County, who sentenced defendants in two different cases to the maximum possible penalty. Titus was charged with reckless driving causing death and several serious injuries after he crashed his semi into numerous vehicles while checking his facebook feed. In the companion case, Linklater was charged with OWI causing death after she became intoxicated, veered left of center, and crashed her vehicle into an oncoming car, killing the other motorist and seriously injuring the passenger.

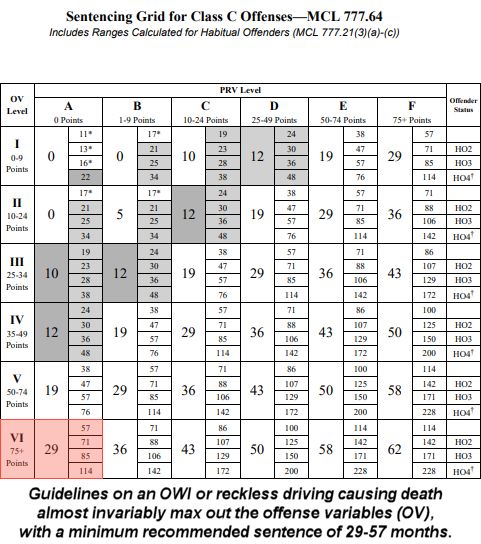

In both cases, the trial court departed from the recommended minimum sentence range of 29 to 57 months and imposed a maximum sentence of 10 to 15 years. (Ten years is the absolute maximum sentence that the judge could give because Michigan has a 2/3 rule detailed by MCL 769.34(2)(b) which states that “[t]he court shall not impose a minimum sentence, including a departure, that exceeds 2/3 of the statutory maximum sentence.”)

Judge Lambros justified his departure in both cases because he believed that the death of a victim and serious injuries constituted an aggravating factor. He also pointed to the reckless nature of the driving in the reckless driving case and the intoxication in the OWI causing death case. But these are elements of the offense, and these factors are anticipated by both the charge as well as the guidelines. These are not aggravating circumstances since they are elements of the crime. The Michigan Sentencing Guidelines calculate a defendant's prior record variables and the offense variables, culminating in a guidelines range, which is presumptively appropriate.

In both cases, the defendants were first time offenders, and they expressed remorse and apologized to the family and friends of the victims. Several people at sentencing demanded the harshest sentence in the reckless driving causing death case, and in the drunk driving causing death case, a former classmate of the victim said to the local news "I think she should have been given more time." Judge Lambros could not have legally sentenced either defendant in these consolidated cases to more than 10 years.

It is easy to say that a convicted criminal should have received a tougher sentence, but it seems that the judge was apparently persuaded by the public outcry in these two cases. "Judges are supposed to be men of fortitude" according to the US Supreme Court, but there is little doubt that they are sensitive to the "winds of public opinion." Craig v Harney, 331 US 367 (1947).

Harsh, punitive judges have always been popular ... at least from a distance. Think of Judge Roy Bean ("The Law West of the Pecos"), and his reputation as a hanging judge. Judge Rosemarie Aquilina, the judge in the sexual abuse case of Larry Nassar, drew praise and criticism when she proudly proclaimed that she signed Nassar's “death warrant" and said that she “might allow what he did to all of these beautiful souls—these young women in their childhood—I would allow someone or many people to do to him what he did to others.”

On a high profile case where the defendant received a light sentence, the Los Angles Times commented on sentencing guidelines, remarking that:

"For too long, well-publicized cases ... sent a fearful and angry nation in the opposite direction, removing much of the judge's traditional discretion. The resulting system [using mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines], ... locked up too many people for too long while giving merely the illusion of being unbiased. Many states and the federal government are in the midst of a broad reevaluation of the criminal justice system and are returning some discretion to judges."

While the family of a victim and many members of the public might desire a harsh sentence, judges are supposed to dispassionately follow the law. The unfortunate truth is that we already have the world's largest prison population. With only 5% of the world's population, we incarcerate 25% of the world's prison population. In other words, our judicial system is already exceedingly harsh.

For those in the public who advocate for even more punitive sanctions, no one wants to pick up the tab. Michigan already allocates over $2 billion annually to the Michigan Department of Corrections, and those costs have increased 219% since 1979. The state increased spending on education by only 18% during that same time-frame.

Harsh sentences hide behind a thick layer of hypocrisy. We say, "Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us," when we really mean "punish the other guy but forgive me." By way of example, in the 48th District Court in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, Judge Kim Small hands down harsh sentences for first time drunk driving offenders. Facing a 45 day jail sentence (which is not unusual in Small's court), a middle age professional might risk losing everything - job, home, marriage, etc. With the tables turned, a person who used to shout, "lock her up," might find himself outraged at the insensitive nature of the punishment.

I am not suggesting that OWI causing death should always result in a two and one-half year sentence or that a reckless driving causing death should not be considered serious. Clearly, both of these offenses are very serious, as are most felonies in Michigan. But we do not automatically impose the maximum sentence because that ignores the law. If Michigan's citizenry wants tougher penalties for drunk driving causing death, that is better addressed by the Legislature, with Michigan's citizens understanding that we all agree to be equally bound by that law. We cannot expect judges to impose sentences that are based on passion, prejudice, or a recent poll of public opinion, and we neither want, nor need, judges who will ignore the law as it is written.

Weight:

-20